Best known for her arresting, almost ecstatic performances of the 1970s in which she handcuffed herself for hours to fellow artist,Tom Marioni, or blindfolded herself for days, artist Linda Montano was one of the first artists – along with peers like Marina Abramovic, Tehching Hsieh, Vito Acconci, and Gina Pane, to name a few– to explore the physical limits of the body and its capacity for endurance as a legitimate form of artistic inquiry. I first encountered her – appropriately enough – in the Mercer Street window of the New Museum back in its SOHO days, where she’d “installed” herself the first day of every month for a seven-year period, listening to a specific tone for seven hours, and interacting with the public in what she called “Art/Life Counseling”. It was the last year of the performance which she’d begun in 1985, and my first year in New York. Later that year, as a intern at the museum, I was able to get my hands on a copy of the related – and sadly, out of print – 1986 exhibition catalogue, Choices: Making An Art of Everyday Life , organized by Marcia Tucker (New Museum founder and director), where I learned that from age 19 to 21, Montano lived in a convent, leaving – ironically and poignantly enough – when her body couldn’t take anymore: “I left the convent because I was dying of anorexia. I was very nonverbal, something I’ve worked on since as an art form. I couldn’t communicate in the convent. Everything was held inside, so my body spoke because I couldn’t. I was choking down information and not getting it out. My body spoke for me and decided I wasn’t doing well. I weighed eighty-two pounds.” Despite this trauma, Montano’s interest in spiritual practice and modes of thinking continued, including several years of study in Zen Buddhism, and though her relationship to Catholicism cooled, its ideas of suffering and devotion – embodied best by the saint/nun paradigm – have continued to inform her work. Wanting to better understand this link between her artistic identity and spiritual practice, and the martyr-like underpinnings it suggests, I invited Montano to discuss her work in this context, and to my delight, she agreed.

JH: One of the reasons I thought it would be interesting to talk to you about the idea of martyrdom is because I know your recent work was built around the daily care of your father, who you nursed until his death, and also because of your renewed commitment to Catholicism. Contrary to the body-based endurance works of the 1970s for which you became quite famous, your work now suggests a kind of healing that derives from taking on the suffering of others rather than just your own.

Etymologically, the word martyr comes from the greek word μάρτυς, or mártyrs for witness; a person who called to declare her or his allegiance, traditionally religious, is then persecuted for it. But the concept of martyrdom also shares many psychological associations with masochism; with self-sacrifice, surrender, and the transformative even ecstatic aspects of pain. Mystics, for example, not only welcome affliction, they pray for it; suffering for them becomes a form of purification and catharsis. How do you see yourself and your work in relation to this idea of choosing to suffer?

LM: Jane thanks for doing the martyr research and for thinking about me!!! I took care of my Dad for 7 years, 4 of those were just shopping, driving, etc. but three were as his 24/7 caregiver. This was what my entire practice as an artist prepared me for…that is, this DAD ART was the culmination of my practice. Dad died 2004 and while I was with him I used the video camera as a place to hide behind and to gather hours of tape (before his stroke) as we’d begun collaborating on a tape together. I continued thisprocess afterwards with his unspoken permission, and it became a study in old age, sickness and death. Was it incredibly difficult, yes. Was it the most heart opening experience of my life and therefore an important experience, yes. Was I a martyr, willing to die for my dad? I guess so.

How did this interest in the Passion of Christ begin? From a misreading of Catholic Theology. You see, we had a very intense Crucifix in our Church which I used to look at and pray before, and one day (when I was around 11), I said, “You suffered and died for my sins and for me. Ok, not in a spirit of competition but maybe yes, in that spirit, let me, Little Linda , suffer EVEN MORE THAN YOU, JESUS, so that I, Little Linda can bea sinner.”

So that infusion of wrongness went into the subconscious and I have spent these 68 years making sense of my wrong indoctrination. Making weird and unbelievable life and art commitments became my norm and my way to BE A SAINT, albeit an ART SAINT! Roll the camera to now…and as a returned Catholic, I am re-seeing and re-doing this commitment to my soul by changing my focus and definition of “saint” so that instead of creating suffering, I am watching it happen to me, and yes, calling it art. See You Tube, Linda Montano: Dystonia. May all beings be free of self-inflicted suffering because that is ego out of whack!

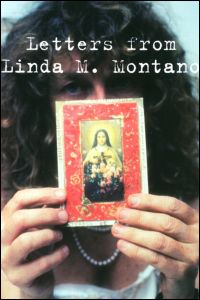

For more information on this intriguing, seminal performance artist check out her book, Letters from Linda M. Montano, an anthology of writings published by Routledge (2005). “It provides an autobiographical and historical record of Montano’s artistic practice over the last thirty years, collecting together stories, fairytales, letters, interviews, manifestos and other previously unpublished writings. At the same time, the book acts as a ‘how-to’ manual for aspiring performance artists, offering practical guidance for students and a range of exercises that Montano has used in her teachings and workshops.” You can also check out http://www.danielwasko.com/livemediafeeds/index.php for a wonderful visual archive of her work, and for a great interview on her year-long collaboration with Tehching Hsieh (1983-84) in which they were tied together by a rope, go to: http://www.communityarts.net/readingroom/archivefiles/2002/09/year_of_the_rop.php

http://www.lindamontano.com