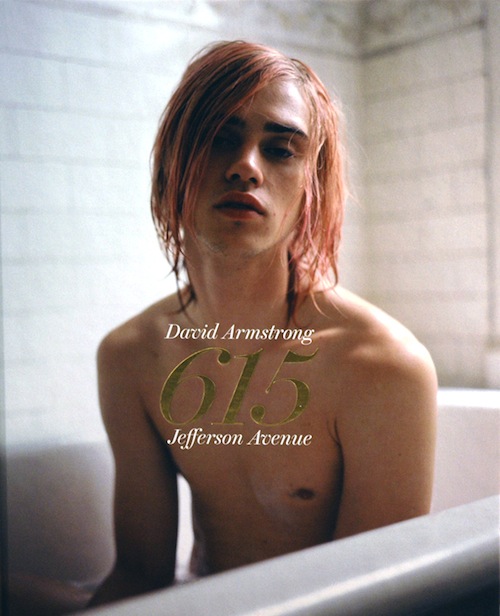

I have this vision of David during one of our visits in his Bed-Stuy home, sitting in a high-backed chair, smoking a Newport, gazing into the late day sun. It was July 11th, one of the hottest days on record, a heat wave with temperatures in the high 90s, the heat index in the 100s. He’d tried to cancel because of it, but I’d already gotten a cab before the email reached me. And there we sat on the second-floor of his 5-story brownstone where he shot many of the images in the book we were to talk about, filling the light-saturated room with our cigarette trails, talking of cats, sex, and poor health. And of course about the boys who inhabit his work, house, heart and mind. A photographer long associated with “The Boston School,” a group of artist friends (Nan Goldin, Mark Morrisroe, and Jack Pierson, among them) who in the late 1970s developed a kind of snapshot aesthetic loosely defined by saturated color and raw intimate portraits, Armstrong has spent the last decade creating highly prized commercial work for fashion editorials, bringing to the glossies and the masses a doleful eye for beauty. The elegiac, often transcendent tone of his photographs, particularly the portraits of young male models captured in his latest monograph, 615 Jefferson Avenue (Damiani, 2011), taken before and after officially commissioned shoots, conveys more than mere beauty, however. Suffused with longing and an acute sense of the ephemeral, there is among the gorgeous young faces and carefully arranged tableaux, a feeling that time and memory are paradoxical twins, never in synch, but always connected. Similarly, there is in the artist’s old-world manners and unironic love of glamour, a timeless appeal to the fugitive. Nevertheless, David is nothing if not candid, his words like his images steeped in an eloquence as forthright as it is often sad. A self-declared shut in, who prefers to spend most of his time at home, he is refreshingly unapologetic about behaviors others might find socially unacceptable. In a recent New York Times interview, for example, he openly concedes to drug use: “Jokingly, I [used to] say that if I reached 50, I would start doing everything again,” he said. “But it turned out I did. I started using again in 2002. Am I a functioning addict? I’m functioning enough.” It’s that candor and the tender love for a youth forever spent yet obsessively sought in the very rooms where we talked that led me to discuss with David the making of 615 Jefferson Avenue.

JH: The title of your book is the place where all the portraits in it were taken, but 615 Jefferson Avenue is clearly more than a number on a street. For anyone who’s had the pleasure to visit, or look carefully at the atmospheric lair that enshrines the pretty boys in your melancholic pics, your 5-story house smack in the middle of do-or-die Bed-Stuy, is a theatrical wonder of sprawling rooms and shifting light — as much a character in these works as the models themselves. Perhaps even a surrogate for yourself? How do you think your relationship to “home” has informed the images in the book?

DA: Faithful Jefferson Ave expresses more of me than I have the balls to in situ, and I thoroughly believe it stands as a faithful lieutenant to any with even a cunt hair of visual perception or emotional sensitivity. It’s more “me” than I am, mortgaging me rather than the reverse. I shall never escape the charms it holds, the resonance of all that’s happened here. Its fragile beauty and that of the light inhabiting its rooms and halls. I will never leave this place until the dark parade escorts me out. But yes, this house is definitely a prominent participant in any picture made here, and often in a manner beyond my control. This place is me, I’m in its possession.

JH: One of my favorite things about the house is the large, eccentric collection of stuff that you’ve amassed there. Moving through the maze-like corridors of its endless rooms, one sees all these groupings of objects where the Belle Epoque meets deshabille chic, arranged ephemerally on tables and under bell jars. I too obsessively collect shit, from cat whiskers and subway posters I steal to space age tchotchkes and vernacular pics, but there’s rarely any order. You manage to imbue these tableaux with a narrative and aesthetic potency such that many become sculpture/art. Does the process of arranging the different elements that comprise these more finished “works” mirror that of the boys you portray, arrange, and collect in your book?

DA: In fact, these processes mirror one another very little. Both bodies of work function as self-portraits but in such different ways. The piles of junk that take form over hours, days, months, and years furnish the one place where I still can work in an organic way, let something develop, contemplate it, then change it, add or subtract from it, move it or dismantle it. And more recently to sometimes say “that’s it, it’s done, there it is.” Very Mrs Dalloway.

JH: How then do the photos take form? And why are all the subjects young beautiful boys?

DA: The choice of subject, the time, the place, and then whatever evolves; mutations have occurred over the years but those fundamentals remain. I’m always scared before a portrait shoot the way you might be before an assassination. So much has to do with putting the person at ease, enough so they might open themselves to you in some small way. Jumping into the water is how I think about commencing any shoot. I honestly have no idea what i’m doing or where we’ll end up. As the only other participant, the sun can have as much to do with it all as either the model, the house, or myself. There’s an arc, it can be as short as an hour or as long as a day. In some cases, like the serial versions, it can go on for years with a single muse. Usually a point comes where I’m totally lost, the pictures are dictating themselves, I love that. There’s a climax and then you shoot a bit longer, wanting to cover yourself, though you know the moment’s passed. And all my subjects are not young beautiful boys. Glancing back I’d say for every four boys I’ve shot, I’ve shot a girl, in many cases much more interesting photographs. Also, I spent nearly five years primarily photographing places. Scalo published a monograph of these land and cityscapes, “All Day, Every Day” in 2002. And I’ve continued to make them until now. I spent nearly four years working on a series of portraits of hustlers at Stella’s and the hotel Sherman directly preceding and overlapping the earliest of images in 615, none of them beautiful in the conventional sense, or all young for that matter. In my own estimation the best of my most recent work are interiors, images of this house, and my house in the country. Reshooting what are nearly two dimensional piles of other images, many of the tableaux of objects you spoke of earlier, and many just of rooms, windows doors, mirrors that change with the times of day and the seasons of the year. A lot of these were shown at Arles two summers ago when I’d just begun them. They continue to interest me more than anything else I’m currently doing. The selection of images in this book is obviously very specific and as I feared the idea behind it required a lot more clarification, but then you can never underestimate the stupidity of people. So what’s the diff?

JH: Lol. Well, in Ryan McGinley’s interview with you, he foregrounds your long-term friendship and relationship with Nan Goldin, a pivotal association others seem to systematically invoke as well. Does that ever get on your nerves — to have writers/curators/critics continuously fasten your work and its influence to Nan’s?

DA: No it doesn’t. I never would have picked up a camera had it not been for Nan. Beyond that nan and I brought each other up from the time we were 14, this isn’t folklore, it’s fact. We have a bond that for better or worse cannot be broken. We taught each other how to see in the confines of Harvard Square and Beacon Hill. Years later in Berlin her largesse allowed me the privilege of a post-graduate holiday that lasted for three years, affording me the freedom to do nothing other than relearn how to make images. And further still, had it not been for Nan no one would ever have seen the pictures I made. I remain in awe of her raw and staggering genius as a creator of images. I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Nan. We share a love, the dynamic of which is strange to say the least, baroque even, but so are most friendships worth having. So yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus.

JH: Still, while the work shares a similar sensibility, there’s often a painterly, somber quality to your portraits (the boys never smile, for example) that recalls old masters, and distinguishes itself from Nan’s technicolor paeans to abject glamour through emotional restraint and sexual sublimation, wouldn’t you agree? What personal experiences and art historical references most account for this difference in tone, in your estimation?

DA: I think Nan’s photographs are primarily linked with painting in so far as her use of color running in perfect tandem to the content of th, something not easy to pull off, and I don’t think intentional though undeniably true. As expressive as any other formal element to a painter is the use of color, the same is true of Nan. I’m not a good colorist and still pretty new to it. It took several years for me even to understand an image was working precisely because of the color. I think my pics also allude to painting, but more in terms of the use of line, compositional elements, and the handling of light. I generally find looking at paintings to be a far more transcendent experience… in the hierarchy of art forms, photography actually registers very low on my list, if at all. Henry Geldzahler once said we’d all be a lot better off if we realized photography was a hobby and not an art form. Had I not been the hapless fellow of 19 I was and had any courage, I’d have continued my pursuit of painting which is the reason I went to art school in the first place. But when all’s said and done, any good work of art needs to be judged on the amount of felt life it contains, painting or photo, mine or Nan’s, restrained or in your face, emotion is what it’s about. Of course that’s the world according to me, and judging from the mountains of crap being turned out these days, I’d say this notion of “art” was co-opted several decades ago. Sic transit gloria mundi..

(published in Huffpost as well: https://blogger.huffingtonpost.com/mt.cgi?__mode=view&_type=entry&id=1142479&blog_id=3)