(also published in Huffpost)

The desire to inspire others to keep on going regardless of the suffering and hardships encountered in life is a noble pursuit in art, and a tall order at that. But the desire to inspire others to find in their suffering and hardship the makings of beauty and healing — well, that’s magic in my book. In the realm of contemporary art, there tends to be a divide between the two as the political and spiritual rarely align in a single practice. Franklin Sirmans did a great job in 2008 highlighting some of these rarities in his group exhibition at PS 1/MoMA “NeoHooDoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith”. Focused on the use of ritual “as a means to recover ‘lost’ spirituality and to reexamine and reinterpret aspects of cultural heritage”, it included Tania Bruguera, James Lee Byars, Jimmie Durham, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, David Hammons, Michael Joo, and others. Earlier that same year, AA Bronson collaborated with a group of young gay male artists – Item Idem, Michael Dudek and Scott Treleaven, among them – in “School for Young Shamans” at John Connelly Presents, an exciting installation-cum-experiment that emphasized a return to the idea of artist as healer via the sixties paradigm of the “free school”.

Still, sometimes it takes a sustained, intimate examination of one artist’s journey through a lifetime of trials and tribulations to really appreciate and understand the power of ritualized healing. A person who has – without didactics or heritage – instinctively sought to reinvent himself through the self-revelation that pain is transformation. An artist like Hunter Reynolds, whose friends regularly refer to him as the proverbial cat with nine lives because he has endured so much and achieved even more. So on the occasion of his recent solo exhibition, Butur, at PPOW Gallery, I sat down with Reynolds to talk about the magical nature of an art practice that in the aftermath of two AIDs-related strokes, and three summers spent at a spiritual retreat for gay men, led the artist to create such an inspiring, beautiful body of new work.

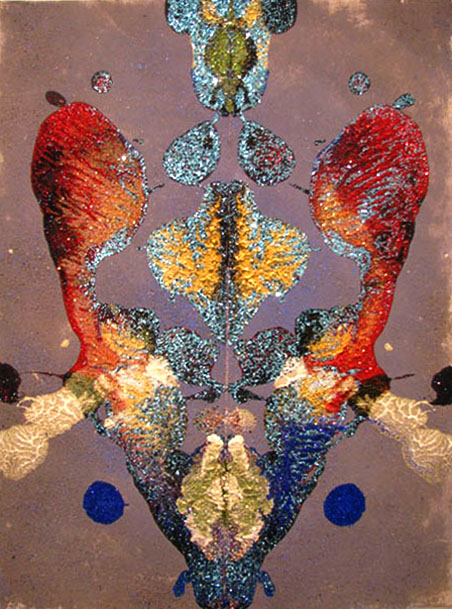

JH: Your Rorschach paintings were created after a stroke-related paralysis forced you to learn to use your left (non-dominant) hand, and are also nostalgic in origin, harkening back the diagnostic tests you underwent as a learning disabled child, right?

The Star of Markab Glitter Mask, 2011, ash, glitter, acrylic, polymer on arches archival cold press, 20 x 15 inches, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

HR: Yes, in 2003 after 3 years of what I thought was a midlife crisis, which started for me at the age of 40, I began a process of recovery. Recovery from 911, recovery from my addiction to crystal meth, recovery from my self and the loss of hope I felt about my sudden inability to process my own pain. The pain in life that we often try to cover up or avoid is the kind I have always been good at recovering from in order to reinvent my self. It has been my modus operandi. I have always believed that no matter how difficult life is, it is a beautiful thing to be alive and there is something better on the other side of that pain. Making art has been the tool I use to process and deal with my pain as well as transform it.

Shaman Mugak Totem Collage, 2009, acrylic and thread on paper, 44 x 18 inches, Courtesy PPOW Gallery

This is a skill, a discipline I learned very young, in fact. My grandmother taught me to paint in oils at the age of 4 years old. This saved my life in many ways. I was good at it, and it gave me a language to communicate and structure the chaos and abuse I was experiencing on a daily basis.

Taking a paint box out into nature, to the forts I built, became a means not only to escape my painful reality, but to create a new and better one. This practice became my obsession and also helped me process a world that was literally a blur for me as it wasn’t until the age of 8 that someone figured out I needed glasses. Couple that with a daily life of chaos, and the fact that I was severely learning disabled (unable to functionally read or write), and you can imagine how strange it was just navigating survival.

The Star of Scheat Glitter Mask, 2011, ash, glitter, acrylic, polymer on arches archival cold press, 20 x 15 inches, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

In school I acted stupid and sat in an unresponsive state of silence most of the time. I was subjected to tests and tutors and remedial classes that I usually failed at, and was sent to a few psychiatrists for evaluation because people thought I was a “retard”. This really worked for me. In the end everyone got so frustrated they just left me alone.

Ink blot tests were one of tools used by therapists to evaluate me. I was able to respond to them verbally and describe what I thought I saw. I remember that it was fun, like looking at the sky and seeing animals and faces in the clouds.

The doctor who I was sent to – because no one had heard me speak for a few months -told my parents that I was not stupid, or unable to communicate, but just needed a lot of support and special attention. Well that fell on dysfunctional deaf ears.

JH: So how would you connect this return to a crucial visual and psychological moment in your past – symbolized by the Rorschach series – to the need to start over physically?

Well, like I said I was unable to see properly for years and had learned to compensate for this disability through silence and painting. It was my third grade teacher who changed all that. She had written something on the board and called on me to answer a question. It was my first week in a new school and I was sitting at the back of the room. She asked me several times and began to yell at me, “LOOK AT ME, LOOK AT ME NOW!” I began to cry. Then I said it for the first time in my life, “I cant see the board” . She asked me to look in her eyes and I could not even see her face. She was just a big blob. She held up her hand and asked me how many fingers she was holding up. I said I could not see her hand. At that moment she walked me to the clinic and I had glasses 10 days later.

Suddenly I was able to process all this information and my learning curve sped up. This event was both visually and psychologically a seminal moment in my childhood. So after the strokes I went through a process of looking backward, and studying my notebooks and sketchbooks to see how I might reinvent my creative process with my left hand. Drawing and sketching and working in notebooks has been a continual part of my practice over the last 30 years, even though many people perceive me as a conceptual performance and photo based artist. The Rorschach test ink blots were something I found repeatedly scattered throughout my sketchbooks, sod when in 2008 I had the opportunity to turn a barn in Westchester into a studio, the ink blots seemed the perfect way to get back to mark-making and image making. I just simply started throwing paint on paper and folding it in half though everything – from cutting and tearing to sewing them – was a great challenge. I had to figure out one-handed techniques for every aspect of the process, which was both time-consuming and often very frustrating. It took me three years to finish the series.

JH: And what about the use of the glitter?

HR: Glitter! what can I say about it other than it sparkles, and that makes me happy.

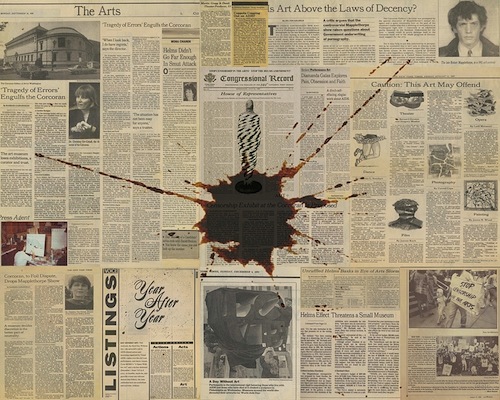

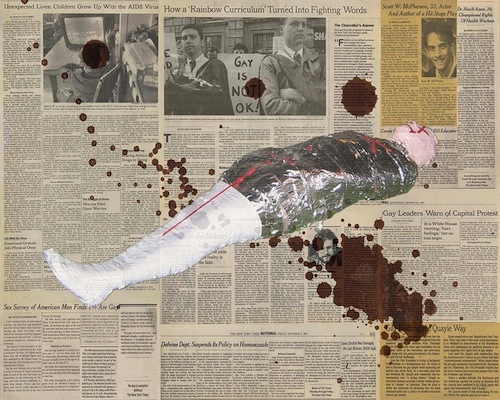

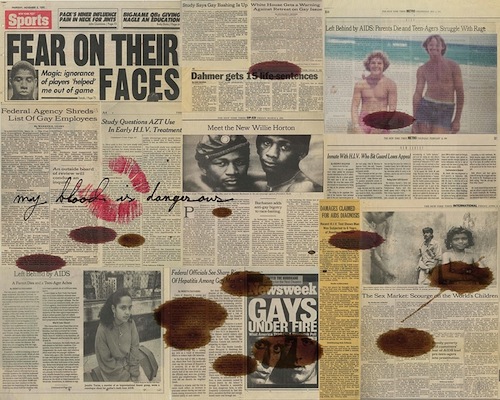

JH: Yes, and perhaps the glitter represents the kind of optimism Roger Denson referred to when discussing the sewn newspaper grids that comprised your 2011 series, Survival AIDS, shown at Participant Inc. In many of them electric colored mummies and lipstick kisses float above a blood-splattered graveyard of words, suggesting a kind of transcendence. As Roger put it: “riddled as the work is with the signage and iconography of death and disease, Reynolds keeps the message clear of becoming an elegy of surrender to the forces that could bury our hopes.” One could relate these works, and their methodical/cathartic impulse to the new work – the Rorschach paintings, and fire totems alike – via this tone of hope and optimism, don’t you think?

Congressional Record (page 19), 2011, c-prints and thread, 60 x 48 inches, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

HR: , Interestingly enough Survival AIDS and the fire totems in my current exhibition were created side by side during the same time period. Both came out of an energetic healing process conducted over three summers at the Easton Mountain Retreat Center in upstate NY, a spiritual retreat for gay men, where I created fire rituals that became the literal basis for these sculptures. So although these two bodies of work look very different, they both reflect aspects of my healing process, and a desire to use art a as life-long healing process that will inspire others to see that no matter how difficult and painful life can be, it is worth living and there is is hope. Everyone must find hope in something. I find it in art.

JH: That’s what makes your work so incredibly intimate, I think. It must have been very intense going through all those newspaper headlines and stories chronicling a very difficult period in gay history, and your own personal life. What led you to create that work?

Gay is Not OK, 2011, c-prints and thread, 60 x 48 inches, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

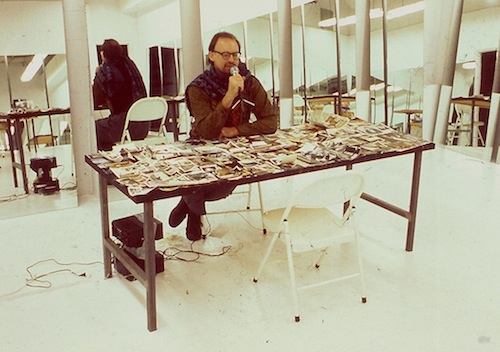

HR: Between 2006 and 2009 I was looking back at my creative practice over the last 30 years, and I was really looking at everything. One of things I was struggling with was photography. I’ve been taking pictures since I was 18 years old, thousands of them, mostly 4 x 6 inch prints that document my life. In the past, I thought of this practice in diaristic terms, using the photos in installations where I’d put them on tables, stack them in shoe boxes, or arrange in family photo albums – the way you would find them in your grandmother’s trunk.

“Can We Talk”, 1992, family table/performance site, Hunter College, 2008

I’d already begun to sew them together into tapestries – what I call Photo Weavings – by the early 1990s. Some were metaphorical portraits of people who died of AIDS, others were of nature and light documenting my body in place and time.

After my strokes, and the loss of the use of my right hand, I realized cameras were made for right-handed people. Because my camera was just too big and bulky, I decided to use Photoshop to create an installation called the Disaster Series that encompassed my experience of 9/11, Hurricane Wilma (which destroyed my house in Florida), and surviving AIDS. I proposed an installation for Momenta Art in Brooklyn titled “Hurricane Hunter Hurricane Wilma” that explored this. I found this box with tons of newspaper clippings related to AIDS, and the LGBT community’s efforts to end it, which I’d incorporated into my work of the early 1990s, and had been collecting since the late 1980s. I was astounded at how many there were. I spent a year and a half scanning thousands of articles and revisiting all these newspaper headlines, reliving this history with the profound realization that I was still alive to read them 20 years later. The resulting installation, Survival AIDS, was the most difficult conceptual project – other than the Memorial Dress – that I’ve ever made. It took me two years to create the photographs in Photoshop, about 4000 of them, a very rigorous activity. It was not only about reinventing a physical way of working but also about returning to a history of conceptual activism and chronicling a crucial time in gay history. It became very emotional for a while as I was reading many of the articles and obituaries etc. for the first time. Eventually, I had to adopt a kind of clinical detachment to get the project done.

Fear On Their Faces (page 7), 2011, c-prints and thread, 60 x 48 inches, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

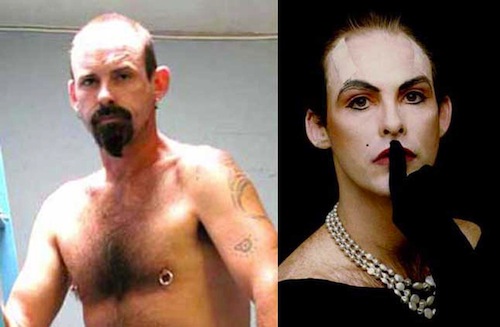

JH: There seems to be a similar reciprocity between the mummification performances, with their simultaneous sense of endurance and transcendence, and the Memorial Dress/Patina Du Prey works (1993-2007), which also function as public ritual. The latter reference traditions of the sacred andogyne, specifically the berdache (Native American) myth of the two-spirit being (usually a male who identifies as female), and interestingly have been included in your current exhibition – an entire room devoted to them! – to contextualize the current work. Can you talk more about the significance of Patina du Prey?

HR: The birth of my alter ego, Patina du Prey, in 1989 was a project that stemmed from the negative and homophobic environment of my childhood. My mother was a 1950s beauty queen who’d saved her crinoline bell-jar shaped dresses. I was always fascinated watching her put on make up and get dressed. Also, my grandmother and I would make clothing for her dolls and my grandfather painted portraits of the Southern Bells at Cypress Gardens. So it seemed natural that I would want to put on her dresses. When my mother was at work, and I was home alone, I tried them on. I would spin around and let the crinoline blow in the wind and it felt so freeing and natural. It occurred to me at the age of 9 to do this in front of my friends who were mostly girls. So I did, we had a blast, and my first drag experience was a positive one. But when the girls went home and told their parents, the latter called mine who then punished me by banning me from playing with them. This was very traumatic and I never put on a dress again.

Until 1989 when I decided to confront the negative effects of this early experience by simply documenting the removal of my beard and applying make-up. At the time, I was a member of ACT UP, and found out that I’d been HIV positive since 1984. I also co-founded Art Positive, a group combating homophobia and AIDS phobia in the art world. My installations began reflecting these activist and political experiences, which I tried to bring into galleries and institutions.

Patina du Prey Self-Portrait, 2000/Patina du Prey Drag Pose Series, 1990, Photo Michael Wakefield, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

So Patina du Prey was born as a vehicle of healing for my own drag-phobia! And for two years I experimented with taking drag out of its kitschy context and making public appearances in the streets of NYC, and at art openings. I found out that it confronted people on a variety of levels. Sitting on the subway, or simply having coffee at McDonald’s became a political action. What surprised me the most was the hostile and aggressive reaction I received from the art world. I actually had people push me.

This all culminated in my first one-person exhibition in NYC called DRAG at Simon Watson in 1990. I exhibited a selection of the Drag Pose photographs, and created two performance sites in the space, The Vanity and The Cage. Every day I sat in the gallery at the Vanity in front of the Queen Mirror getting ready, putting make-up on, and talking with people. Then I would get into The Cage, which was suspended, and dance over the heads of visitors.

It was while performing in this cage for 5 hours a day for four weeks that I studied the psychological and emotional reactions viewers had to this image of a man in a dress. People could not look at me and would often just ignore me completely. Looking at me was confrontational. I realized that if I veiled my face then they could stop and really look at me. So I got several yard of tulle and and used it as a tool to allow viewers access to my image and their feelings around transgender and drag.

Patina du Prey Drag Pose Series, 1990, The Drag Cage Performance, Simon Watson Gallery NY, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

This performance changed my own perception about what I wanted to communicate with this project. I realized that I didn’t want to be a traditional drag queen nor did I want to co-opt the female body. I wanted to explore feminine and masculine codes of dress and what most focused these intentions was a book written by cultural anthropologist, Serena Nanda, Neither Man Nor Woman: The Hijras of India. Serena heard about my exhibition and came and talked to me while in the cage about gender identity, and her experiences of living with the Hijras, the name for third-gendered people in India. She sent me her book, and it changed the direction of my Patina du Prey project for the next decade.

I realized I needed to create a container, a vessel for for my body to function as metaphor for healing, using my 3rd gender identity, Patina du Prey. The form this took was a life-size music box with me standing as the rotating doll. The dress would be designed for my male body. It would not have breasts but would have the classic female dress codes.

I accomplished this in 1992 with the Banquet dress, which was printed with hair and blood, and made in collaboration with Chrysanne Statacos for our project, The Banquet. At this event, I rotated in the dress for 6 hours during a performance of feminist readings by various guests gathered around a meal being served off a live male nude.

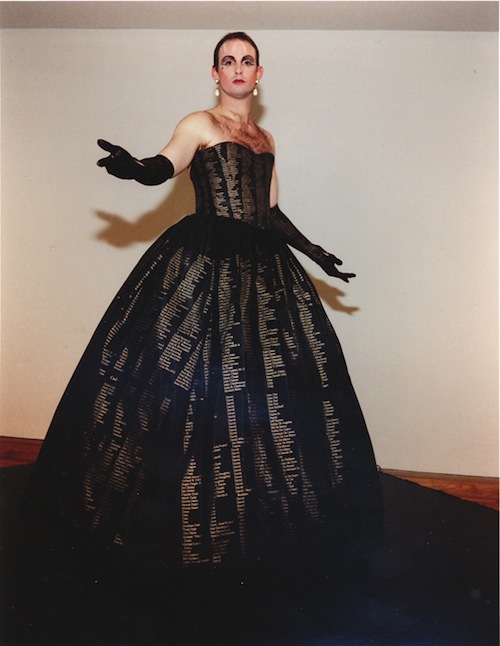

So over the next 7 years I made 7 more of these dresses as sculptural performance works including: The Patina du Prey Memorial Dress, 1993, printed with 25,000 names of people who have died of AIDS; The Ascending Dress The Love Dress, 1994, inscribed with my hand-written diary texts and love stories; two different Dervish street performance dresses for the Goddess Within Project, with Maxine Heneryson, 1993-95; and finally the Mourning Dress,1997, featured in Butur.

Patina Du Prey’s Memorial Dress, 1993-2007, printed with 25,000 names of people who have died of AIDS, Photo by Maxine Henryson, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

The knowledge that my body through art became a energetic sacred site of healing was first experienced in my 1993 performance of the Memorial Dress at the ICA in Boston. I performed the turning dervish dance for almost 5 hours in front of a crowd of about 2000 people. During this trance, others also had very cathartic emotional reactions, weeping, convulsing and collapsing. Usually this happened because they were just coming to an art performance at which they may have found the name of a loved one inscribed on a dress being worn by a transgender person absorbing their pain while they experienced it.

When I was 30 I realized I wanted to use my ability to transform my own pain and the pain of others through my art also because of the words of a dear friend on his death bed. Ray Navarro told me that I should have no fear of dying of AIDS and not let it control my life, and to express this fearlessness in my work. So that is what I did.

Butur Installation View, Patina du Prey’s Mourning Dress, 1997, photographs from I DEA The Goddess Within Project, by Maxine Henryson, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

The Memorial Dress was performed and exists as a sacred site of healing in which I stand and turn as a transgender shaman. For many years I would never use that word, “shaman”. It has so many connotations and can be misused and easily misunderstood. Although I knew that was exactly what I was.

Unlike the Memorial Dress where acts of healing took place because of and within the context of the work itself, My exhibition, Butur, reflects an act of healing for my self. Living as a long term survivor of HIV and AIDS, overcoming strokes, shedding my masks and replacing them with Glitter masks that reflect my happiness, the Rorschach’s reflect my struggle back to beauty while the fire totems exist to absorb my pain as reflections of healing, and a life transformed.

Shiva Lingam, Fire Altar, Easton Mountain, 2010, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

JH: Can you tell me more about the process of the fire totems? How did they get made, and what was their impetus?

HR: The Fire Totems are the result of fire rituals that I conduct at Easton Mountain. Since the early 90’s when I was living in Berlin, I’ve been studying energetic spiritual healing with contemporary gay shamans. The spiritual journey I have taken for the last 20 years has included the study of Sufi Whirling Dervish dancing with Dieter Jarzombek, who has also worked extensively with Annie Sprinkle. With him I learned actual ritual techniques of healing, which included meditation, fire rituals, and vision quests in sweat lodges. So I was able to experiment and use these techniques in my performances in the Memorial Dress and The Goddess Within. These healing experiences happened within a structure I created to allow strangers and I to intuitively interact and experience some sort of healing together.

The Transformation of Butur, 2011-12, Easton Mountain Retreat Center NY, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

Creating ritual around and within my art has been a way of working that has taken many forms and intentions. I had not really worked with fire before I went to Easton Mountain in 2006. There I met Joe Monkman a contemporary gay shaman working with the Peruvian tradition of fire ceremony as a transformative process. After taking several workshops with Joe I wanted to explore what I had learned and experienced on my own. So in 2009 I took 3 months out of my city life and got a small cabin in the woods at Easton Mountain and set up an out door studio in the woods at a scarred fire pit. I began making private rituals and fires every day. I saw that I was interested in creating the fire altar, the wood that was to be burned as an art object. I would elaborately decorate with paint, glitter, fabric and other special things. Sometimes I spent days making the altar that was to be burned. Making this beautiful precious thing that you are going to destroy as an offering to fire gods for healing was a powerful experience.

Mandala, 2012, Installation View/Butur, PPOW Gallery, Courtesy of PPOW Gallery

In the summer of 2010 I began to perform ritual fires for community gatherings at Easton Mountain. There was a different fire each week and I would create elaborate fire altars with different intentions and themes related to various retreats.

So it was that summer when I was making totems by stacking chunks of wood to create the centerpiece of the altar structure that I discovered that while most of them would burn away (sometimes over the course of days), some of them would remain intact in the end as a charred object. I began to see this as an artifact of the ritual fire embedded with all the spiritual intention of the fire. I saw them as sculptures.

Butur, Installation View, 2012, PPOW Gallery, Courtesy PPOW Gallery

Butur the fire totem sculpture in my Exhibition at PPOW was created as result of these ritual experiences. It’s a four part process that takes several months to complete. The building of the fire altar, the ritual burning, the reconstruction of charred remains as an altar, and finishing the final object, which in the case of Butur required carving the wood with a grinder, and then sealing it with a lot of polyurethane and glitter.

The process of my fire rituals will be published in my forthcoming book, Burning a Path to Healing, and in the video, Butur.