“A bestiary is a type of book, common in the medieval era, that catalogues animals. Medieval bestiaries typically included both real and mythological creatures, thereby incorporating natural history, cryptozoology, and legend. Plants and minerals were also sometimes included in bestiaries…The idea of the bestiary also survived past the medieval era, and modern examples can often be found. French illustrator Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges are two more recent authors of bestiaries. Reference bestiaries are often available for fantasy games such as Dungeons and Dragons. If you are curious about what a medieval bestiary looked like, there is an interesting, interactive website featuring material from various medieval sources at bestiary.ca.” – wisegeek.com

Bestiaries

In the medieval period, animals were allegorical by god’s design. “As the eagle rejects any of its young that cannot stare unflinching into the sun, so God will reject sinners who cannot bear the divine light” – that sort of stuff. Physiologus, an Alexandrian text written in the 2nd-3rd century, was the first collection of explicitly Christian animal lore, and one of the most widely-distributed books in Europe after the Bible. The basis for the bestiary, or “book of beasts”, Physiologus included about 50 animals in its encyclopedic reach. Adding to this texts from other sources, the Bestiary expanded the lexicon, and offered more worldly interpretations as well.

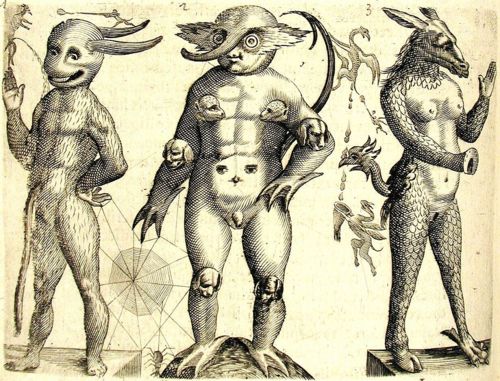

Fortunio Liceti [Fortunius Licetus], De Monstruorum Natura…, Padua, P. Frambotti, 1634 [first ed. 1616]. Giovanni Battista Bissoni is the author of all engravings.

The production of bestiaries was particularly popular in England and France. Symbolic and often fantastical, its animals became instant media sensations, appearing in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, tapestries, carvings, etc. St. Bernard of Clairvoux, writing in his Apology around 1127, summed up the clergical disdain for their popularity: “What profit is there in those ridiculous monsters, in that marvelous and deformed comeliness, that comely deformity? To what purpose are those unclean apes, those fierce lions, those monstrous centaurs, those half men, those striped tigers, those fighting knights, those hunters winding their horns? Many bodies are seen under one head, or again many heads to one body. Here is a four-footed beast with a serpent’s tail; there a fish with a beast’s head. Here again the fore-part of a horse trails half a goat behind it, or a horned beast bears the hind quarters of a horse. In short, so many and marvelous are the varieties of shapes on every hand that we are tempted to read in the marble than in our books, and to spend the whole day wondering at these things rather than meditating the law of God. For God’s sake, if men are not ashamed of these follies, why at least do they not shrink from the expense?”

Interestingly, its because most artists/illustrators were unable to actually observe the animals in question that the images they created became literally figments of the imagination, their reference points being limited to a kind of visual hear-say. Alongside the usual suspects like unicorns, dragons, griffins, and centaurs, there were serpents with two-heads (Amphisbaena), barnacle geese that literally grew from trees, and a beast whose horns could move at will. The idea of the mythological hybrid creature has always been of interest to me, and of course exists in many cultures besides the Greeks.

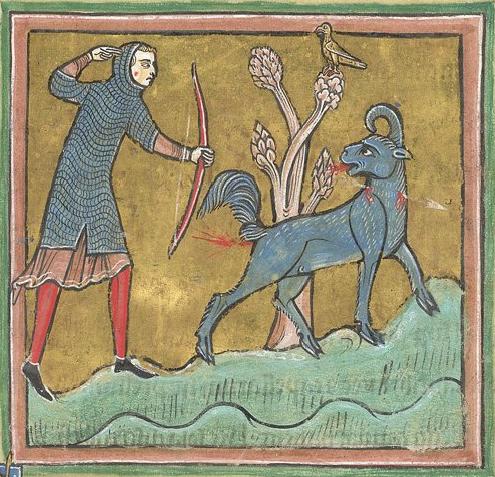

Kongelige Bibliotek, Gl. kgl. S. 1633 4º, Folio 54r

So what’s the relevance of bestiaries to today’s culture? Novelist Nicolas Christopher responds: “I believe they are very significant. First, they serve as important source documents in the history of natural science. Europeans, beginning with ancient Greek and Roman chroniclers like Aelian and Pliny, who had never seen a tiger, hyena, or crocodile, began cataloging these beasts they encountered in explorers’ tales. Aelian’s Animalia, for example, is one of the first zoological encyclopedias in the West. Second, they tell us a great deal about how the human imagination was at work when ancient man, trying to order the world around him literally and figuratively, created myths in which animals, animal hybrids (like the hippogriff, which is part horse, part griffin; or the peryton, which is a bird with the forelegs of a deer; or the chimera, which is part lion, goat, and dragon), and purely invented animals like the phoenix and makara played crucial allegorical roles. The survival of these myths is important to our understanding the development of the human psyche and the origin of our collective memories. They are sagas of redemption, revelation, and illumination that pertain to all men. In short, the animal myths collected in bestiaries are one chapter of the immense history of the human soul, which is why every civilization and culture—Tibetan, Mayan, Persian, Egyptian—produced bestiaries.”

I am drawn to them not just because I’ve always loved the idea of the hybrid creature in mythological constructions, but also because I cant help but wonder if some of these animals did in fact exist, and/or were perhaps the palimpsests of prehistoric memory? I know its a long shot fantasy, and even when they were most popular, not everyone believed they were real. Still, I’m pretty sure, swayed by the authority of contemporary and ancient sources alike – from Pliny and the Old Testament to Aesop – that had I been born in the Middle Ages, I would’ve been one of those that did, for the sheer pleasure and terror of imagining their supernatural powers! Anyway, here are two of my favs…

The Asp:

“Kongelige Bibliotek, Gl. kgl. S. 1633 4º, Folio 53r, Asp: serpent that can plug its ears against the enchantment of music “In some versions the asp guards a tree that drips balm; to get the balm men must first put the asp to sleep by playing or singing to it. Another version holds that the asp has a precious stone called a carbuncle in its head, and the enchanter must say certain words to the asp to obtain the stone.” – http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast268.htm

The Bonnacon:

“The Bonnacon is a beast with a head like a bull, but with horns that curl in towards each other. Because these horns are useless for defense, the bonnacon has another weapon. When pursued, the beast expels its dung which travels a great distance (as much as two acres), and burns anything it touches.” — The Medieval Bestiary