I met Max Carlos Martinez, or Maxy as I call him, about 15 years ago via friends who went to Skowhegan with him, a network we’re both still close to. He, like I, often had big loft parties back then, and we avidly attended each other’s. He often reminds me of how I brought to him one grapefruit for a birthday gift, all wrapped up. I remember him sitting with me at one of mine as I put on make-up discussing the anguish of love before the onslaught of guests arrived. Our friendship though was really cemented by my love of his work.

When I first saw Max’s paintings, I was instantly enamored. The vibrancy, the patterns, the undercurrent of irony and wit, and the longing they possessed moved and stimulated me. Mind, body, and heart, the way it should be. When he had his first solo show after 25 years in NYC at Christopher Henry, my review in Time Out New York felt like an act of justice, an acknowledgement long overdue.

Just a few months ago, another friend had a show at the same gallery, and in the basement hanging in the office was a Max Carlos Martinez. I found myself so happy to be in its presence, missing my friend and his work as much as I did, that I began to drag my friends down there to look at it, and promptly reminded the dealer what a great artist he was.

A few years ago, Max lost a close friend, and a longterm lease that had allowed him to live cheaply in NYC, as an artist should, for 30 years. As most of us know that lifestyle was becoming extinct in this town, and while I hang on, hustling constantly as a determined freelancer, my rent stabilized lease is key to that success.

So rather than capitulate, Max decided to move back to the southwest where he hailed from, and got a residency in Sante Fe, where he still resides. To stay connected, Max and I often exchange long personal sometimes even harrowing emails about day-to-day struggles, dating scenarios, and other stream-of-consciousness, finding in each other the rare audience for such missives in a day and age when texting and tweets reign. Wanting to capture the same wit, heart, and soul of those emails, and catch up with his recent work, I decided to do the following interview. As you’ll see, it reveals the brilliance and resilience of my dear friend, Maxy, who embodies for me the very integrity of the word, “artist”.

JH: How has moving to New Mexico changed your work or process?

MCM: I began my current body of work in 2004 in order to address contemporary issues using historic American iconography, I wasn’t about to sit in my studio painting Condelezza Rice or Bush Jr. I am big fan of historical studies the irony the subterfuge, how we convince ourselves that the end is always near, how we belong, how we accept our past, how we deny it.

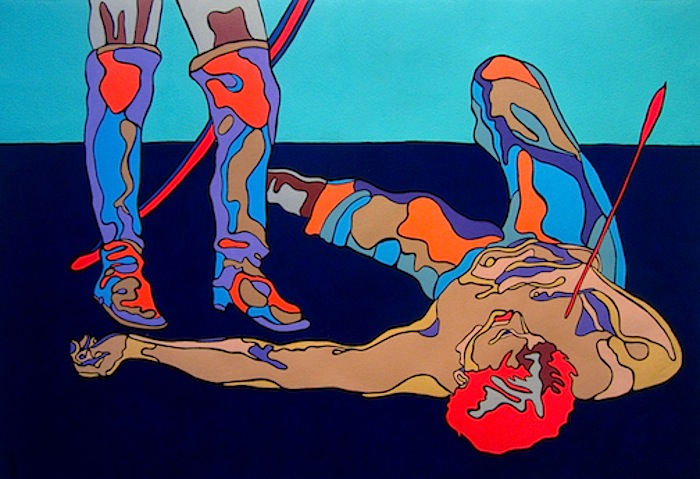

By 2007 the content was focused on the formation of the American West, Cowboys and Indians, guns, greed, stereotypes. I had no idea that I would be living in Santa Fe now or how my work would be received here. The audience for my art is rarely ever at the top of the list for why I paint. I was lucky enough to find a terrific place to stay, a historical hacienda on Canyon Road in the middle of a hundred galleries that has been renting to artists since the 1930s, hell even Georgia O’Keefe lived here.

The atmosphere of my home is very intoxicating. A 10,000 foot high mountain looms in my backyard, there is quiet and yet just enough noise to satisfy a New Yorker. The natural light that pours through the massive windows has electrified my palette, the colors have grown brighter, the patterning has opened up and I am spending a lot more time mixing colors and thinking about how to arrange them.

JH: The lines are not as compact and detailed, its true, and seem more solvent somehow than optic. Are the colors chosen as a result of these experiments or do you choose a palette for allegorical purposes as well?

MCM: Sometimes there is an allegorical sensibility to which colors I use, a certain blue background will be used to create a feeling of dusk, a foreboding drama where the characters are frozen in a perpetual state of violence that may or may not occur. Other times I am without the funds to purchase paint, so I use whatever it is that I have available. Some mixtures are intended to revive the life of the subject, most of whom are anonymous, whose stories will never be known. But for the most part it is just a spontaneous and instinctual reaction to the moment, while I do think about which color to use on an unfinished piece, I might say, red, that’s it, but I will never know which red it will be until I come up with the mixture.

JH: What’s the biggest pro and con of living there versus NYC?

MCM: It is easier to be broke here, only slightly cheaper than NYC, but I get respect and support. My rent is always late, the landlord understands and tolerates me and this vision of mine. I recently met with the director of the foundation that runs the residency, he wanted to know if there was some way to set up some payment plan so that I could be on time with money. I said, listen honey, I have been living like this for thirty years, if you can figure out a way to make sure that my rent is paid by all means please do.

The economy here is stagnant, the galleries cater to tourists, people come to live but do not stay, or they come here to retire and when I approach those folks about buying either their walls are full, start a fucking archive, or they have given up on collecting. I stopped looking for work in a gallery after so many failed attempts, on one interview with a gallery owner, he wanted to know if I could afford the look, five hundred dollar jeans, pressed shirts, a three hundred dollar cowboy hat, hell no.

The interest in my work is flaccid at best. I do have support thankfully, people who respect me as an artist and friend, a host with an open door policy. The artist community can be very insular, sometimes when I hit the openings I am the youngest one in the room. There is no Metropolitan museum where you meet your friends on a Friday night, look at art and flirt with handsome young men.

JH: What are you working on now?

MCM: I paint everyday, sometimes for just a couple of hours, other times all day long. I am continuing with the Western theme, which sells better in NYC and L.A. If you are going to work with that theme here it had better look like Remington or abstracted wild horses or landscapes that evoke the historical regional masters of the genre.

I have been working from images that would have been seen in the tabloids of the 1850s. Recently I have become inspired by Hollywood, the ideals that were popular in early twentieth century Western movies. Men were men, Indians were savages, women were helpless, Mexicans were greasy, the cowboys were always sexy and potent. I am inspired by the irony of it all, the manifest destiny, the assumption that as a nation we can have whatever we want, if it is foreign we will demonize it, if it does not belong to us we can take it, maybe we could take more, have more and become less in the process.

JH: The methodical nature of your work seems to operate as a kind of meditation while the palette is often near psychedelic. How do the two come together for you, in your estimation?

MCM: My first experience with being bullied was in Pre-K, that girl with unformed fingers who would drive her claws into my hands when the teacher wasn’t looking. I didn’t want to go to school, I had a huge family, there were so many sources of inspiration, why bother. But in kindergarten when the teacher brought out the finger paints, boom, I was done, I knew all that I needed to know, I was an artist.

I grew up in what I understood then to be some sort of idyllic American life, it never really was, but I continued drawing, we were so broke that I drew on any paper available with the school supplies we bought at the five and dime. I saw The Agony and the Ecstasy, Moulin Rouge, Lust For Life on the afternoon TV show Dialing for Dollars. Then came the years of being ostracized because I was obviously gay to everyone else.

That is when my studio process began. Everyone in my family wanted to be an artist, so my desire was not shunned. I could smoke some cheap weed, sit alone, draw, block out the walls falling around me. Everyone said that I was crazy, weird, different, I actually embraced those ideas, yeah I was going to be different and pursue this vision. We were so broke that you couldn’t afford a dream.

Then we took acid, smoked dope, the THC powder period, the eventual coming out during the Bicentennial, my dad’s suicide, the paint that I bought with his military survivor benefits, the canvas, the plans to move to NYC which is where I ended up in 1981. Six months later the homosexual cancer scare, the dying, the death, then I met Jason who would support me as I taught myself to paint well.

When I was a kid my family up and moved from Albuquerque to some distant California land, that transition from the dry dusty plateau to the wild life of 1969 where Pop Art reigned changed everything. It all just came together, I knew very early what I wanted, witnessed some terrible times, knew that I was going to die someday, why not focus on this dream, no matter what was going on around me.

JH: Like many artists who try to live off their work, you know well the pitfalls of being an artist, yet everyone who knows you knows you live to paint. Does this reality reflect in the content of the work, or just in the journals you keep?

MCM: I knew that I wanted to be a visual artist when I was six, began reading shortly thereafter. I started keeping journals when I was twelve, inspired by the lives of so many people around me, the stories that I overheard. I began taking pictures, shooting videos on my dad’s 8mm camera, drew constantly, wrote hundreds of letters to my older siblings who moved away. I needed a dream, had one, followed it, fulfilled it, convinced everyone that this life of mine was valid. The content of my work only reflects all of that.

JH: So stories from the past, your experience following a childhood dream to be an artist inform your work and not responses to the here and now?

MCM: I use the past and historical imagery to create a connect the dots game to current topics, obviously gun violence is an easy one, sexism, racism, homophobia, the ideal of a governmental leader as a heroic figure. My dream is why I wake up everyday and paint regardless of the rent, the past due electric bill, empty cupboards or anyone’s opinion of what I should be doing, like getting a job.

JH: What been the biggest misconception about your work over the years?

MCM: Where it was coming from, that I am an angry Latino reclaiming some lost culture. My first successful paintings in the early 80s were geometric precisionist architectural pieces, they were very lovely and did not require an intellectual explanation. Then I went totally abstract, paintings based upon the urban decay, yeah, everyone got it, no problem.

In the early nineties I began the autobiographical family series, the paintings that would take me months or years to finish, the work that would get me into residencies, get published, and finally 17 years later my first solo at the Tweed Museum, my first museum retrospective.

By then I had gone through the artworld mill, had to defend my work when people asked why should they care about a poor self-taught artist from Albuquerque, why don’t you move back if it is so important, someone said, why don’t you move back? To me that series was about becoming an American, a hundred years of my family’s assimilation, this is my story and it comes from love and the idea that this story is valid and should be shared.

Now people think that I am satisfied with being miserable, that I cling to the notion of being a “starving artist”. That my work is still rooted in some angry point of view from an outsider of the American cult, that I am from Mexico, no darling, I am an American artist and this is part of our history that we all share.

JH: You’ve been writing an autobiography for a while now, can you talk about that endeavor, its relationship to your work?

MCM: I have been working on my autobiography since I was twelve. I knew then that I would, does my life matter, will anyone read it? When I was a kid there were so many great storytellers but nobody ever wrote anything down. I did, collected these histories, surely my personal archives could have been more succinct but I had to listen when the elders were drinking because that was when the stories really came out. I needed to be observant, focus on my goals, learn to listen and remember what it was that I heard. I have always told everyone that I would eventually write about them, it was never a secret.

But I also wanted to tell my own story, how I came from that dusty history, how I found that early inspiration, finger-paints kindergarten, how an artist grows, is nurtured, everything that went on around me, the sixties, the seventies, disco, sex, NYC, the plague, being poor, having money, the East Village apartment in the eighties, love, the lofts in Tribeca, the nineties, breaking up, new love, a fellow artist, the fights, no money, the break ups, the war on terror, maturation, leaving the city, going back to my roots, the prodigal son, being broke, you can’t go back, painting daily, not paying my rent, the stress, the parties that I throw, Santa Fe, the life of an artist.

I got what I wanted.