I never think to re-circulate my old writing, previously published stuff, but wtf, I watch artists promote the same work in different contexts all the time, which I like when its random, or the result of an unexpected encounter with an old work they forgot about, or find – in the long glance of retrospection – strange or interesting or nostalgic.

I came across this 2001 interview I did with Monica Bonvicini in just that way, by accident, and it took me down memory lane. It was for Artforum online, and I came across it googling artists engaged with architecture and gender. Kind of a sweet surprise, as I’d completely forgotten about it (big surprise, ha)! It reminded me of my trip to LA that year, where I saw the show we discussed, though sadly I can’t remember where:(

Here it is as a link, the cut-and-paste below is easier to read, and includes better images, only one of which, sadly, represents the installation I saw. There weren’t anymore online. Its a great work, though, one that made me think again about Bonvicini’s intrepid use of gay S & M imagery at a time when it was still outre or at least before harnesses became a catwalk staple.

Consider it my version of throw back Thursday, and if you want to know more about her work, Phaidon did a great book on the artist, and I threw in a few more pics of other, later work. HAPPY FALL!

Monica Bonvicini talks to Jane Harris about architecture and the iconology of construction workers.

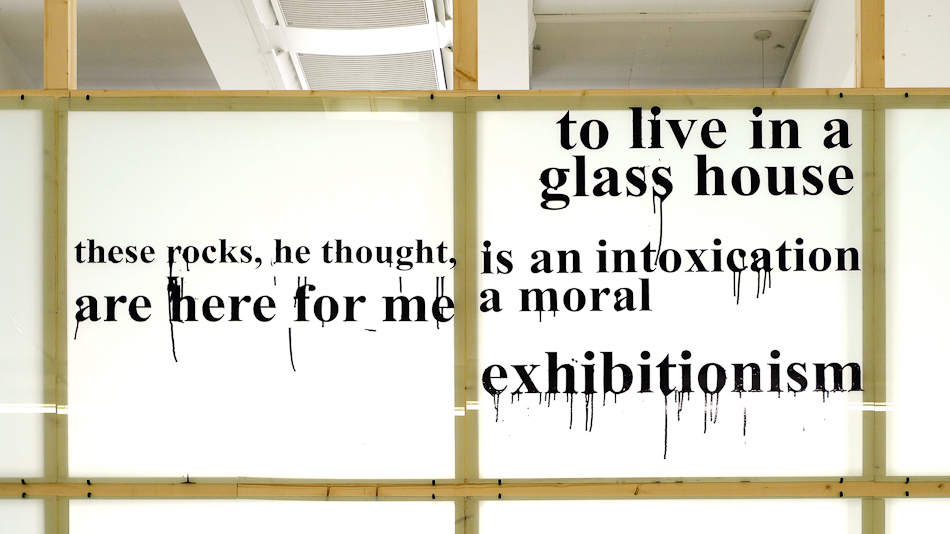

For several years now, Monica Bonvicini has been something of a heckler, taking aim at the granddaddy of all aesthetic boys clubs: architecture. In her 1999 Venice Biennale work, I Believe in the Skin of Things as in That of Women, the Italian-born artist turned Le Corbusier’s well-known comment on its head, vandalizing the facades of a boxlike room she had built and covering the broken walls with graffiti.

Quotations from other famous male architects, such as Auguste Perret and Adolf Loos, were juxtaposed with obscene words and caricatures of naked men holding square sets, masturbating, or gazing at bejeweled women. Eternmale, 2000, installed at the Kunsthaus Glarus, featured slick white chairs and tables designed by Willy Guhl (from bent panels of Eternit, a mixture of cement and cellulose), an electric-blue carpet, ambient music from porno films, a video monitor displaying a burning log, and Picasso’s Tête de Femme (Head of a woman), 1963. A parody of a playboy pad from the 1960s, the room offered the ultimate guy space for chilling out, seducing chicks, and refueling the testosterone.

Bonvicini’s sense of humor is incisive and often chilly, sort of like Bruce Nauman on dry ice. Her themes—the libidinous charge of architectural space and the often sexist presumptions that underlie its theory—are considered with critical distance but are tweaked empirically by her lifestyle. She has spent over a decade dividing her time between Los Angeles and Berlin, two cities very active in the promotion of new architecture, especially the latter, where the buzz about building a new Berlin has been as loud as the cement mixers and drills, not to mention the hoots and hollers of construction workers whom women cross the street to avoid.

These Days Only a Few Men Know What Work Really Means, 1999

For Bonvicini, construction workers are, on the one hand, laborers who toil with no glory; on the other, purveyors of aggressive masculinity. But it is precisely the complex class and gender issues they embody that make them interesting to her. In Fuckeduptimes, 1999, Bonvicini interviewed bricklayers, asking them questions like “What does your wife/girlfriend think of your rough and dry hands?” and hired them to build minimalist structures in limestone.

This past May and June, Bonvicini presented a number of works at the inaugural exhibition of The Project in Los Angeles. One of these, These days only a few men know what work really means, 1999, delved into the contradictory symbolism of construction workers. The piece explores the psychosocial dynamics of advertising billboards, which the artist has overlaid with images of gay sex and quotations taken from the simultaneously public and private world of Internet chat rooms.

Both Ends, Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel, 2010

Jane Harris: Tell me about your piece These days only a few men know what work really means.

Monica Bonvicini: I find it interesting that construction workers are so popular in gay erotica, but, at the same time, are well known for their extreme heterosexual behavior. There are other connotations in the piece as well. When I first showed it at the the Art Basel fair in 1999, I used portable aluminum walls that belonged to the fair, and kind of mocked the idea of an art-fair “statement.” The metaphor of a bunch of construction guys fucking each other (images I found in a gay porno magazine), and the misspelled quotations I took from the Internet, were hard to digest for quite a number of viewers. And then there are the two black-and-white pictures of Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves, both of whom are literally wearing their own architecture in the form of models. But as you say, I had been working with construction materials, on construction sites, and with construction workers for a while.

JH: You did a piece at the MIT List Center for which you made an impenetrable structure from chain link, cinder block, and Home Depot wood trellises. Aren’t you working with Home Depot fences for another work, Turning Walls, 2001?

MB: The piece at the MIT group show was Turning Walls—the same piece I am showing in Grenoble.

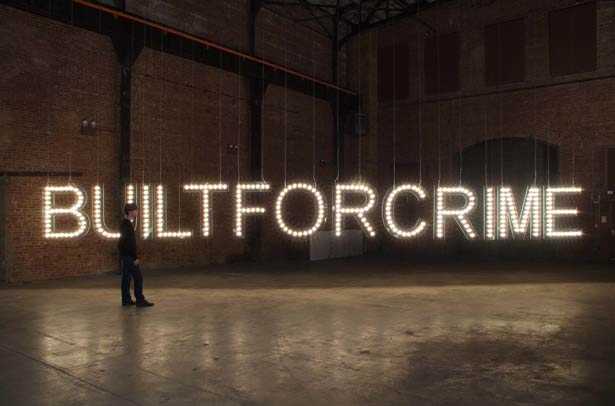

Monica Bonvicini, Built for Crime, 2006, SculptureCenter, New York, Broken safety glass, bulbs, 5 dimmer packs, lan box, 4′ x 40-1/2

JH: I really like BEDTIMESQUARE, 1999. It’s a realization of a drawing you did some time ago, isn’t it?

MB: Yes. BEDTIMESQUARE was based on a drawing from the series “Smart Quotations,” 1996. The work relates to a piece of Carl Andre’s. Because of the industrial materials and the inflatable mattress in the middle, it is, metaphorically speaking, like sleeping in a Minimal sculpture. The bed, along with the window and the wall, are classical representations of feminine space. You know, the history of the bed is very interesting.

JH: Especially in performance art. Chris Burden, Gina Pane, and Vito Acconci all used beds or bedlike structures to draw connections between the body and the institutional frameworks in which it operates. So did Valie Export. What are you working on now?

MB: I just opened the show at Le Magasin in Grenoble. I’m also preparing a public art project for the Aussendienst in Hamburg, which deals again with the language of commercialism and its relation to art. I’m going to produce billboards developed by Scholtz & Friends, one of the biggest advertising companies in Europe, for buses and subway stations in Hamburg.

JH: Will you use construction-worker imagery again?

MB: Maybe. Why not?